Back to the King's Head for this very interesting revival of Colin Spencer's Spitting Image - the first openly gay play performed in the UK back in 1968 after the decriminalisation of homosexuality and (presumably) the relaxation of theatre censorship, and never since revived.

It played for two months to packed houses at the Hampstead Theatre (greeted with much tutting by the Evening Standard), and transferred to the West End. In the disapproving atmosphere of the times however, the play could not find a publisher, and disappeared. It's amazing that Adam Spreadbury-Maher, artistic director of the King's Head, discovered a script in the Oscar Lewenstein theatre archive at the V&A Museum, and hence this revival was possible.

One half of a gay couple falls pregnant and the play explores the consequences both for their relationship and in society. What is amazing is at the time it was written the idea of gay couples bringing up children was totally unthought of - the play uses it as a metaphor for coming out - but now of course in the era of gay marriage it's pretty topical.

Spitting Image's giddy and surreal social satire sits well in the context of Orton and Stoppard. I actually thought the satirical element worked best - the couple squabbling over dirty nappies and relationship issues less so. The huge concern the play demonstrates over crushing state surveillance is sadly right up-to-date. Nothing's changed there.

The acting was all on point and brought out all the fun of the piece. The set design aimed for minimalism but actually was quite tricksy and distracting with actors having to carry props on and off awkwardly all the time. At least in the first half Sally Ambrose entertained us while this was happening with her groovy 60's dance moves. In the second half she became a character in her own right, mooning after Alan Grant's Gary, the gay man struggling against the odds to keep his relationship and child.

Friday, September 02, 2016

Thursday, September 01, 2016

Tribal Art London

The Tribal Arts London fair 2016 is now on in The Mall Galleries until the 4th September. It's a great opportunity to catch an eye-popping spread of Tribal Art all under one roof - areas covered include Africa, Asia and the Pacific. Entry is free but bring your wallet in case you are tempted to buy any of the masks, figurines, bronzes, textiles, ceramics or jewellery on display.

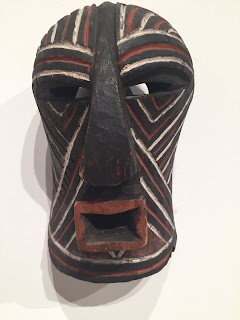

I dropped in to have a look and here are a few of the things that caught my eye. First of all, obviously, some African masks:

(Songye masks from the Congo)

Another Congo mask

A Pende dog mask

A spectacular Sowei/Nowo mask from Sierra Leone

This Fon bronze of a lion with its prey I thought was very elegant.

Exotic head gear!

A fascinating 'power object' - we in the West are more familiar with lovers' locks on bridges - a very different sort of magic I imagine.

The Zulu are very famous as a tribe but actually their art is quite rare - here is a fascinating 19th-century staff with a lion being hunted (top) and a zulu snuff box made out of horn with a metal lid.

Finally, this Ethiopian headrest I thought was striking in its beautiful shape and patina, with highly intriguing metallic adornments and repairs.

I dropped in to have a look and here are a few of the things that caught my eye. First of all, obviously, some African masks:

(Songye masks from the Congo)

Another Congo mask

A Pende dog mask

A spectacular Sowei/Nowo mask from Sierra Leone

This Fon bronze of a lion with its prey I thought was very elegant.

Exotic head gear!

A fascinating 'power object' - we in the West are more familiar with lovers' locks on bridges - a very different sort of magic I imagine.

The Zulu are very famous as a tribe but actually their art is quite rare - here is a fascinating 19th-century staff with a lion being hunted (top) and a zulu snuff box made out of horn with a metal lid.

Finally, this Ethiopian headrest I thought was striking in its beautiful shape and patina, with highly intriguing metallic adornments and repairs.

Tuesday, August 30, 2016

Cut Throat / Camden Fringe

Cut Throat by Jean-Philippe Baril Guerard as adapted by Matt

Cunningham. – London Irish Centre

I caught this play on the penultimate night a week ago now, so this

is a quick late review.

The publicity promised:

"How far can you go in the name of free speech?

Does having the right to speak equal having the right to say everything?

In Cut Throat, the right to speak does not come with a promise that the speech be valid or harmless.

14 characters speak their minds freely about race, religion, relationships, bodies, sex, money, and the meaning of life, without any filter, walking the thin line between comedy and cruelty. An irreverent play that will make you laugh... and cringe."

This was a relatively short, intense play with 14 characters, so

nevertheless quite ambitious as the first production by Trip and Guts Theatre.

The play takes the form of a series of monologues or largely one-sided two-or

three part scenes (mostly loosely unrelated in terms of 'plot' but clearly

related thematically). The audience sits around four sides of a square, and the

actors pop out from the audience's ranks to perform their roles.

All the actors played their parts with evident relish and panache,

and the very wordy play cracks on at a great pace. Stand outs amongst a strong

cast for me were Joseph Rain-Varzaneh as the mugger and Hannah Wilder as the

long-suffering Usher - one of the shortest spoken roles but she appears

throughout the piece as the long-suffering innocent target of the other

characters' nastiness. I can see why this play would appeal to actors -

firstly, each character gets a lot to say and is completely central whilst they

say it, each character has an internal dramatic tension to reveal as the 'real'

inner person breaks through an initial 'polite' or politically-correct outer

shell; and there is external drama in each mini situation too.

We saw this play on the back of Chemsex Monologues, also created

(obviously) around monologues. Monologues are an interesting theatrical device,

notably introduced by Shakespeare to reveal a character's innermost thoughts.

They are at once the most artificial of constructs, breaking any feel of

'realism' on stage but simultaneously the most powerful and direct

communication between actor and audience there can be - really harking back to

ground zero of narration - speaker to listener. There is a tendency in a

monologue for an actor to reach for a kind of declamatory style, which we

thought a bit difficult in Chemsex but this works strongly in Cut Throat. I

think this is because Chemsex the play has realistic fundamental assumptions -

the play is about 'real' characters and plot whereas Cut Throat skews more

conceptual. The characters are very far from realistic, are usually quite easily

identifiable stock contemporary types

- and each scene and character unfolds in a similar way, repeating the

themes of the play almost like an abstract pattern until the climax. My

favourite character, the mugger, is completely surreal, made up as he is of

bravura flights of literary language and philosophy completely alien I would

imagine to any real mugger.

Altogether, a most stimulating evening.

Saturday, August 20, 2016

The Chemsex Monologues

It's not often one hears of an actor playing two roles in different plays at the same time - however, for the last week you could catch Denholm Spurr as Damien/Jean Baptiste in 'The Past is a Tattooed Sailor' by Simon Blow at the Old Red Lion Theatre (through to 27 August) and Nameless in 'The Chemsex Monologues' by Patrick Cash at The King's Head Theatre (last performance tonight).

In fact, make that three roles! (Two different ones in the same play.)

One can only applaud Spurr's energy, commitment and enthusiasm in taking his final bows (after a two hours + performance) at the Old Red Lion and then dashing up Upper Street to The King's Head to don his makeup for Nameless. It would have been fun to catch both performances in a marathon night of theatre, but we took things much more sedately, catching Sailor last weekend (review here) and Chemsex last night after a quick dinner at Belanger on Islington Green.

They are both new gay plays by gay authors performed in pub theatres in Islington simultaneously, but that is where the similarities end.

Sailor is an expansive, nostalgic, traditionally-structured piece whereas Chemsex is much more contemporary in focus and experimental in form. Four narrators appear in sequence with monologues from their individual perspectives on their relationship with Nameless and his story. The audience pieces together Nameless's situation from each fragment - each narrative is slightly unreliable due to their tangential relation to Nameless and the plot line and each character is wrapped up in their own concerns.

This structure gives a sense of urban anonymity and alienation, but also creates a considerable amount of suspense as we follow Nameless's story to its climax. The total separation of the actors also serves to heighten the pathos of Nameless's descent.

The acting was all good, which was so important here when you can't talk of an ensemble. Richard Watkins plays the Narrator - an 'Everygay' sort of character who bookends the play - with breezy charm. Charly Flight is Fag Hag Cath - amusing but very warm and human. Matthew Hodson plays Daniel the Sexual Health Worker - again, a lovable doofus doing his innocent best, a very heart-warming performance. Denholm Spurr's Nameless is the heart of the play and he gives it a terrific performance moving smoothly from humour to the emotional depths.

An urgent and well-considered piece of contemporary theatre; I'm really pleased to have caught it.

Friday, August 19, 2016

The Plough and the Stars

Confession time - I have never seen a Sean O'Casey play performed; nor have I read one. I usually tend to avoid overtly political drama.

However, as 2016 is the 100th anniversary of the Easter uprising I decided to honour my Irish ancestry and indulge my literary curiosity by seeing this revival at the National Theatre (itself mounted to mark the occasion, playing until 22 October 2016).

Reviews have been a bit mixed, so I took my seat with some trepidation. However, I was soon sucked into the world of the Clitheroes' Dublin tenement. This is really a full-blooded, lushly romantic and visually very beautiful production of a traditionally-structured drama. The politics of the play are sophisticated and rooted in the frailty of human character - O'Casey pulls no punches with the British army's occupation and artillery bombardment of Dublin but he is equally harsh on the shortcomings of the nationalists and totally mocks the pretensions of the play's socialist. Nevertheless, O'Casey was a socialist himself and demonstrates a sympathy with all the individual characters - even the British Tommies when they appear are decent blokes who would rather have a cup of tea - and instead he shows how they are all individually trapped in unequal and exploitative social conditions.

It is true that the actors do have varied degrees of success and consistency with their accents, and that some words are difficult to hear. The play is very literary and 'wordy' though, and the directors Howard Davies and Jeremy Herrin were probably wise to sacrifice pockets of legibility in favour of pushing the pace and drama overall.

What charmed me immediately was O'Casey's dexterity in the dramatic arts of foreshadowing, parallelism and contrasting. We first see Nora, the wife of a bricklaying Commandant in the Irish Citizen Army setting a table for tea; in the last act she sets it again in hugely different circumstances with a tragic outcome. In the second act there is a massive contrast between a political meeting outside a pub and the comic antics of a prostitute inside (this caused a riot at the play's premiere in Dublin). The third act, set in the street outside the tenement, starts off emphasising the poignancy of the characters' extreme poverty (Little Mollser clearly on the point of death from Tuberculosis); moves into the broad comedy of everyone looting when the British start to shell the city; followed ominously by the Irish Nationalist fighters with a severely wounded comrade escaping the inexorable British advance; and ending with the crisis between Nora and her husband, with the British soldiers very near. British soldiers make their physical entrance in the fourth act, and despite the horror of British military action the individuals themselves are ordinary guys just doing their job.

From today's perspective one could probably accuse the play of a kind of poverty porn (much played up by designer Vicky Mortimer's exquisite sets) - but on the other hand this is a function of the time it was written in. And surely it is so much more preferable to the Chav-bashing "Benefits Street"-style propaganda of today.

There are excellent performances from the female leads in particular - Justine Mitchell as Bessie Burgess and Judith Roddy as Nora Clitheroe are beautiful, poetic and tragic. Josie Walker as Mrs Grogan is funny and heart-warming; and Gráinne Keenan (Rosie Redmond) and Róisín O'Neill (Little Mollser) shine in smaller roles.

Sunday, August 07, 2016

The Past is a Tattooed Sailor

It’s always pretty exciting to see new work, and a first play by a neophyte playwright.

Joshua, a posh but poor aspirant writer (Jojo Macari), seeks to create a closer relationship with his great-uncle Napier, a bed-ridden ex-social butterfly and fading beauty shut up in his country mansion and living only through reminiscences of his past success amongst the social and artistic elite, as well as his raunchy liaisons with French sailors in Marseilles. Napier’s penchant for rough trade is shared with Joshua, who has a builder’s mate boyfriend Damien (Denholm Spurr) - shared quite literally as the bed-ridden Napier nevertheless craftily manages to put the moves on Damien.

There is good material in Tattooed Sailor, and an intriguing premise, but I felt the writing could have benefitted from further work editing and refining purpose and dramatic direction. I sense a number of unresolved issues in the writer’s emotional responses to these autobiographical events, which sadly accrue around the leading character Joshua, the cornerstone of the entire play: weaknesses in the construction of this character impact the whole piece. Macari struggles manfully with this underwritten and confused role.

Bernard O’Sullivan and Nick Finegan are evocative, stylish and affecting as the older and younger Napiers - Finegan especially evokes the authentic note of a 1930s Bohemian dandy and rake and contrasts pleasingly with the more contemporary Joshua and Damien. Denholm Spurr exudes an effortless animal sensuality and displays rampant sexual chemistry with all three of the other leads - in French too as the titular tattooed sailor in a tryst with the younger Napier.

Overall, this play held my attention and I did enjoy the experience, with the caveat that I ended with feeling a much stronger play is hidden deep within.

Saturday, February 06, 2016

The Winter's Tale

An ‘authentic’ performance in an historically-correct as-we-can-make-it Renaissance theatre could perhaps be a dry, academic affair but I emerged last night from the Sam Wannamaker Playhouse reeling. The visceral drama caused me to question if our contemporary theatre, whether with proscenia or without, with its powerful electric lighting and with all the artifice that modern technology can conjure, is not a waxwork effigy of what REAL drama can be. I’ve emerged confusedly pondering that drama does not depend on faultless sight lines and the most comfortable seats to experience the actors’ art. I had a great seat for Cymbeline in the same space - but I realised then conventional understanding of what a great seat is does not really apply to this space, so I was happy to try a very poor seat this time right up in the gods for The Winter’s Tale.

At first, I was disappointed. I was right at the back on a diagonal to the stage - so I had a seat with a back rest (bench seating otherwise pretty much throughout). I knew the pillar advertised to hamper sight lines was a small slender thing which wouldn’t bother me much but what I hadn’t realised was that the two rows of back-rest-free people sitting in front of me would lean forward. If you are unlucky enough to have a lady with a big hair do in front, that’s half the stage gone, and the pillar takes maybe another 10%. You are up at a very vertiginous rake to the stage, and peering down on top of the actors’ heads through glaring chandeliers. It is surprising just how much light 6 large chandeliers emit - however, even so, its quite dim on stage and even though this is a tiny space and the actors are relatively close you won’t really see their every facial expression very clearly in the golden glow.

However, you will hear even their whispers crystal clear. This space has an amazingly intimate acoustic (all that wood). And although there is a distinct stage area, it feels seamlessly part of the entire space - the audience very much feels physically and emotionally included in the actors’ world. This was particularly true of the trial scene, where Leontes appealed to us as the judges.

Candlelight itself creates an intimate atmosphere which enhances the emotional effect of the performance. This is what weirded me out - I realise our contemporary way of presenting theatre privileges the visual senses of the audience - and in fact bludgeons the eyes by maybe making things too easy to see. The visual restrictions of Renaissance theatre and its candle lighting force one perhaps to use one’s other senses and imagination more and encourage an active emotional participation.

The scene opens in Leontes’ court in Sicilia - as bright as can be, with all the courtiers dressed in white, and with Leontes himself in a gorgeous white doublet with metallic embroidery sparkling in the candlelight. I really admired John Light’s frighteningly rapid descent into psychotic violent jealousy. Rachael Stirling’s graciously statuesque Hermione at first is oblivious to her husband’s suspicions, then is falsely accused and piteously ends up in the trial scene in chains and dirty rags.

By this stage Leontes’s jealous madness has destroyed his entire family: he has broken with his life-long best friend, his son is dead of grief for his mother, Hermione herself has been humiliated in a show trial and has died, and her new-born baby is sent by the king to be exposed in a barren place. All his courtiers fear the king as a tyrant: only the feisty Paulina (brilliantly played by Niamh Cusack) bravely speaks truth to power.

The prison and trial scenes bring the first coups de théâtre. The lights at the opening are all gracious twinkling chandeliers. In the prison scene the chandeliers are all raised high (darkening the stage) and gaolers and prison visitors use braziers and lanterns. The braziers in particular feel rough and crude - visually echoing the King’s madness and the tragic turn of events. Characters are in dark cloaks now, and clever choreography with cloaks and hand-held lanterns throw up stunning effects of light and dark - strongly expressive faces and arms are lit up like a Caravaggio brought to life. Paulina’s and Leontes’ disputes in these scenes are particularly well emphasised.

And then, after the emotional storm of the trial, the chandeliers are all extinguished and the smoking stubs raised swiftly up high - the swinging, eerily smoking chandeliers , together with sound effects, marvellously evoke a storm at sea and on the dangerous coast of Bohemia.

This scene is played in the most complete darkness I have ever experienced in a theatre. We all know what happens next - “exit pursued by a bear” - and this production very nicely extends the tension to its maximum. Antigonus’s wildly swinging lantern is now the only source of light in the entire theatre, and throws careering, pitch black shadows everywhere.

And then after the descent into compete darkness and “the gap of time”, we open up into the light again. Extra chandeliers are lowered onto the shepherds’ festival celebrations, and even a fully blazing fire is carried on stage. Perdita, now fully grown, dances in her dazzling robes and veils with her prince Florizel to the minstrel’s music as if there was no fire hazard. I liked the music, singing and dancing in Bohemia very much: natural and fresh, it is completely organic with the environment and play. Prop’s to Steffan Donnelly’s Florizel - a capering, enthusuastic, slightly immature but very honourable and genial sort of chap. Also one must mention the extraordinary dance of the satyrs. Pagan, oddly disturbing and erotic. The comedic antics of the old shepherd, the clown and Autolycis also lighten the mood and prepare for the reconciliation scene ahead.

John Light pitches Leonte’s remorse just right in the final scene. It’s strange how odd this play reads as text with the king’s rapid emotional reverses but performed well the emotions work perfectly as drama and are believably human. Hermione is restored to us as the gracious queen we saw in Act 1. The play ends, as it opened, with the king kissing the queen.

This is a stunning, fresh and powerful reading of the play in an extraordinary and unique environment. I would urge you to see it if you can get tickets.

The Winter's Tale

Sam Wannamaker Playhouse

Shakespeare's Globe, London

October 2015 - April 2016

At first, I was disappointed. I was right at the back on a diagonal to the stage - so I had a seat with a back rest (bench seating otherwise pretty much throughout). I knew the pillar advertised to hamper sight lines was a small slender thing which wouldn’t bother me much but what I hadn’t realised was that the two rows of back-rest-free people sitting in front of me would lean forward. If you are unlucky enough to have a lady with a big hair do in front, that’s half the stage gone, and the pillar takes maybe another 10%. You are up at a very vertiginous rake to the stage, and peering down on top of the actors’ heads through glaring chandeliers. It is surprising just how much light 6 large chandeliers emit - however, even so, its quite dim on stage and even though this is a tiny space and the actors are relatively close you won’t really see their every facial expression very clearly in the golden glow.

However, you will hear even their whispers crystal clear. This space has an amazingly intimate acoustic (all that wood). And although there is a distinct stage area, it feels seamlessly part of the entire space - the audience very much feels physically and emotionally included in the actors’ world. This was particularly true of the trial scene, where Leontes appealed to us as the judges.

Candlelight itself creates an intimate atmosphere which enhances the emotional effect of the performance. This is what weirded me out - I realise our contemporary way of presenting theatre privileges the visual senses of the audience - and in fact bludgeons the eyes by maybe making things too easy to see. The visual restrictions of Renaissance theatre and its candle lighting force one perhaps to use one’s other senses and imagination more and encourage an active emotional participation.

The scene opens in Leontes’ court in Sicilia - as bright as can be, with all the courtiers dressed in white, and with Leontes himself in a gorgeous white doublet with metallic embroidery sparkling in the candlelight. I really admired John Light’s frighteningly rapid descent into psychotic violent jealousy. Rachael Stirling’s graciously statuesque Hermione at first is oblivious to her husband’s suspicions, then is falsely accused and piteously ends up in the trial scene in chains and dirty rags.

By this stage Leontes’s jealous madness has destroyed his entire family: he has broken with his life-long best friend, his son is dead of grief for his mother, Hermione herself has been humiliated in a show trial and has died, and her new-born baby is sent by the king to be exposed in a barren place. All his courtiers fear the king as a tyrant: only the feisty Paulina (brilliantly played by Niamh Cusack) bravely speaks truth to power.

The prison and trial scenes bring the first coups de théâtre. The lights at the opening are all gracious twinkling chandeliers. In the prison scene the chandeliers are all raised high (darkening the stage) and gaolers and prison visitors use braziers and lanterns. The braziers in particular feel rough and crude - visually echoing the King’s madness and the tragic turn of events. Characters are in dark cloaks now, and clever choreography with cloaks and hand-held lanterns throw up stunning effects of light and dark - strongly expressive faces and arms are lit up like a Caravaggio brought to life. Paulina’s and Leontes’ disputes in these scenes are particularly well emphasised.

And then, after the emotional storm of the trial, the chandeliers are all extinguished and the smoking stubs raised swiftly up high - the swinging, eerily smoking chandeliers , together with sound effects, marvellously evoke a storm at sea and on the dangerous coast of Bohemia.

This scene is played in the most complete darkness I have ever experienced in a theatre. We all know what happens next - “exit pursued by a bear” - and this production very nicely extends the tension to its maximum. Antigonus’s wildly swinging lantern is now the only source of light in the entire theatre, and throws careering, pitch black shadows everywhere.

And then after the descent into compete darkness and “the gap of time”, we open up into the light again. Extra chandeliers are lowered onto the shepherds’ festival celebrations, and even a fully blazing fire is carried on stage. Perdita, now fully grown, dances in her dazzling robes and veils with her prince Florizel to the minstrel’s music as if there was no fire hazard. I liked the music, singing and dancing in Bohemia very much: natural and fresh, it is completely organic with the environment and play. Prop’s to Steffan Donnelly’s Florizel - a capering, enthusuastic, slightly immature but very honourable and genial sort of chap. Also one must mention the extraordinary dance of the satyrs. Pagan, oddly disturbing and erotic. The comedic antics of the old shepherd, the clown and Autolycis also lighten the mood and prepare for the reconciliation scene ahead.

John Light pitches Leonte’s remorse just right in the final scene. It’s strange how odd this play reads as text with the king’s rapid emotional reverses but performed well the emotions work perfectly as drama and are believably human. Hermione is restored to us as the gracious queen we saw in Act 1. The play ends, as it opened, with the king kissing the queen.

This is a stunning, fresh and powerful reading of the play in an extraordinary and unique environment. I would urge you to see it if you can get tickets.

The Winter's Tale

Sam Wannamaker Playhouse

Shakespeare's Globe, London

October 2015 - April 2016

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)