Tuesday, September 21, 2021

Battersea Power Station Station

My old dad, studying electrical engineering at Imperial College in the 1950s, used the drag his cousins after Sunday lunch to the building site of Battersea Power Station - I’m assuming this would be for the extension, when the station achieved its final upturned table appearance. To honour his memory, I visited the brand-new Battersea Power Station Station opened yesterday. It looks absolutely magnificent. I had no idea it would be so huge!

Monday, July 06, 2020

Castle Richmond by Anthony Trollope (1860)

Castle Richmond by Anthony Trollope

Castle Richmond by Anthony TrollopeMy rating: 2 of 5 stars

Marked down severely for his complacency in the face of the totally avoidable Irish famine. Very disappointed that an author I really like and admire could have such a questionable response. Lots to say about this book, but I need to gather my thoughts.

Update 6/7/20

1) Famine

Trollope deserves credit as the only Victorian novelist to address this appalling catastrophe - the worst European famine since the middle ages and the only one in the modern era in Western Europe. The potato blight affected the whole of Europe but it was only Ireland that experienced starvation. Fully 25% of the population either died of starvation or disease, or left the country. Throughout this period Ireland remained a net food exporter. The British government refused to either waive import duty or ban exports, policies which had successfully been applied in the 1780s when the crops failed, and refused to feed the destitute without qualification on the grounds it would encourage idleness. Large "stupid work" projects were undertaken, which Trollope does satirize.

Trollope was stationed in Ireland for his work for the post office, and traveled extensively in the country, so he was writing from direct experience. He dramatizes the excruciating moral quandaries facing concerned wealthy individuals - direct alms-giving was officially discouraged; the wealthy were encouraged to donate via official channels only. He sympathizes with and praises individual good deeds. But he fails to understand that if the official response was adequate individual charity would not be necessary. Several times he explicitly claims the government was doing all it could in the face of an overwhelming natural disaster and could not be expected to do any better. This is untrue, however much the liberal Trollope clearly believed it. As a civil servant perhaps he was constrained to support official government policy. The Liberal Party, standard bearers for 'free market' thinking and policies, were in office at this time.

2) Writing

Trollope's first two novels had been set in Ireland and both had failed. Irish-themed novels were not commercial at this time. Trollope was aware of this (as he states at the beginning of the novel!) but says that as he was leaving Ireland this was his goodbye. The implication is that at some level he felt he had to address the famine and this was his last chance. The famine had occurred about 15 years earlier. Trollope was stationed in Ireland for about 20 years.

Suddenly, he was offered the chance to write the headline serial novel (his first) for the brand-new and heavily promoted Cornhill Magazine. Doctor Thorne had been Trollope's biggest success to date - it sold 700 copies. The Cornhill was to achieve a circulation of 120,000. This was the big time, placing Trollope on the same level as Dickens and Thackeray. However, the Cornhill refused the half-written Castle Richmond and instead wanted another Barsetshire novel. Their deadline for the opening installments was in 6 weeks. Trollope started writing Framley Parsonage immediately.

He juggled writing the two books, finishing Castle Richmond just a few days past his publisher's deadline, possibly the only time this notoriously conscientious writer missed a deadline.

Framley Parsonage is one of the jewels of the Barsetshire novels and made Trollope's name in Victorian Britain. Castle Richmond sank without trace; possibly his worst selling and least read book to this day.

3) Plot

Castle Richmond foregrounds the tangled and somewhat melodramatic romantic and economic affairs of an intertwined group of Ascendancy (ie Anglocentric and Protestant) aristocrats against the backdrop of the famine. Reading today, this juxtaposition jars; the aristo plot is just too obliviously isolated from the horror, as well as being creakily frivolous in itself.

But even on its own terms it fails. The romantic entanglements are really complicated, but Trollope makes the subsidiary characters far more charismatic and interesting than the hero Herbert and heroine Clara, both of whom are conventional and colourless. Herbert vies with his cousin Owen for Clara's hand - Owen is portrayed as handsome, super-masculine, honourable, impetuous and charismatic: in short, all the qualities of a traditional hero. Perhaps his bumptiousness needs a little correcting and this would form the basis of his character arc in a different novel. Not here. Owen is not the hero, no matter how much all the other characters (and Trollope) adore him, and he ends up unfulfilled (possibly), with the consolation prize of Clara's younger brother, Patrick Earl of Desmond.

Trollope is celebrated for his sensitive and psychologically penetrating depiction of unusual situations, relationships and characters, but in this novel these focuses overwhelm the core marriage plot. Clara's mother the Countess of Desmond is the villain of the piece, but she hankers after Owen for herself as well, which makes her situation compelling for the reader (and her struggles with Owen, oblivious to her devotion, much more interesting than anything Clara and Herbert get up to).

I won't discuss the inheritance plot at all, other than to say the melodrama lies largely here. Herbert's father dies very obviously only because the plot demands he does. As character, he is one of those Victorians who turn their face to the wall and decide to die - purely for the convenience of their authors.

4) Homosexuality

A queer academic has excitedly claimed Owen and Patrick as a gay couple. They end the novel travelling up to Norway on a fishing trip, and plan to visit Africa together to hunt big game (pleasingly, bringing to mind a later Irish writer's "feasting with panthers" line). Patrick is in his last year at Eton and Trollope clearly shows he has a schoolboy crush on Owen. Owen however only has eyes for Clara - whilst he is fond of Patrick my reading is he is as oblivious of Patrick's crush as he is of the countess's. The Patrick/Owen relationship seems to me a little plot-determined and functional. Trollope had been a schoolboy at Harrow and Winchester College so he would have been familiar with schoolboy homosexuality. To me Dickens is the Victorian novelist with an authentic queer sensibility.

5) Sectarianism

Trollope is free of conventional English anti-Catholicism to his credit, and satirizes religious sectarianism on both sides. But he presents sectarianism as comedy, which feels particularly hollow in the light of the subsequent history of Ireland. During the famine Irish nationalist struggles did continue, with British infrastructure subject to attack and British landlords killed. Some of the writings of the Anglo-Irish Ascendency from this time, as well as the British, have been cited by some historians as evidence of genocide.

View all my reviews

Saturday, January 21, 2017

Holding the Man

Big Boots Theatre Company are off to a roaring start with this intimate and emotionally searing production of Tommy Murphy's dramatisation of Timothy Conigrave's memoir. Finished only two weeks before Conigrave's death from an AIDS-related illness in 1994, the work is a monument to the love of his life John Caleo. The book won the United Nations Human Rights Award for Non-Fiction in 1995. Murphy's dramatisation has itself won numerous awards and has been made into a film. The last production in London was at the Trafalgar Studios in 2010.

At the Jack Studio Theatre, director Sebastian Palka mounts a fluid, fast and smoothly moving production full of imaginative touches and emotional insight. The intelligent and robust direction means the story never becomes confusing, despite the tiny ensemble cast performing multiple roles, changing costumes and making set changes on stage throughout.

The leads are well cast physically: Christopher Hunter as Tim and Paul-Emile Forman (making his professional debut) as John make a handsome couple with striking chemistry. Hunter emanates an easy appeal and charm which holds the audience's sympathy despite his character's sometimes dubious choices, but for me Forman's luminous John is the emotional bedrock of this work. Written knowingly with guilt as an elegy, John is idealised to a degree which could make him remote - it is a huge credit to Forman who finds the human being in this role and so compellingly inhabits him.

There is good work from the ensemble who mesh strongly as a team. A stand-out is Marla-Jane Lynch, very enjoyable in all her characters but especially affecting in her role as John's mother.

Design and sets are wisely kept low-key and minimalist. I thought the musical and sound choices were appropriate and emotionally helpful, but perhaps a touch too loud in this very intimate space.

Jack Studio

at the Brockley Jack

Friday, September 02, 2016

Spitting Image / King's Head Theatre

Back to the King's Head for this very interesting revival of Colin Spencer's Spitting Image - the first openly gay play performed in the UK back in 1968 after the decriminalisation of homosexuality and (presumably) the relaxation of theatre censorship, and never since revived.

It played for two months to packed houses at the Hampstead Theatre (greeted with much tutting by the Evening Standard), and transferred to the West End. In the disapproving atmosphere of the times however, the play could not find a publisher, and disappeared. It's amazing that Adam Spreadbury-Maher, artistic director of the King's Head, discovered a script in the Oscar Lewenstein theatre archive at the V&A Museum, and hence this revival was possible.

One half of a gay couple falls pregnant and the play explores the consequences both for their relationship and in society. What is amazing is at the time it was written the idea of gay couples bringing up children was totally unthought of - the play uses it as a metaphor for coming out - but now of course in the era of gay marriage it's pretty topical.

Spitting Image's giddy and surreal social satire sits well in the context of Orton and Stoppard. I actually thought the satirical element worked best - the couple squabbling over dirty nappies and relationship issues less so. The huge concern the play demonstrates over crushing state surveillance is sadly right up-to-date. Nothing's changed there.

The acting was all on point and brought out all the fun of the piece. The set design aimed for minimalism but actually was quite tricksy and distracting with actors having to carry props on and off awkwardly all the time. At least in the first half Sally Ambrose entertained us while this was happening with her groovy 60's dance moves. In the second half she became a character in her own right, mooning after Alan Grant's Gary, the gay man struggling against the odds to keep his relationship and child.

It played for two months to packed houses at the Hampstead Theatre (greeted with much tutting by the Evening Standard), and transferred to the West End. In the disapproving atmosphere of the times however, the play could not find a publisher, and disappeared. It's amazing that Adam Spreadbury-Maher, artistic director of the King's Head, discovered a script in the Oscar Lewenstein theatre archive at the V&A Museum, and hence this revival was possible.

One half of a gay couple falls pregnant and the play explores the consequences both for their relationship and in society. What is amazing is at the time it was written the idea of gay couples bringing up children was totally unthought of - the play uses it as a metaphor for coming out - but now of course in the era of gay marriage it's pretty topical.

Spitting Image's giddy and surreal social satire sits well in the context of Orton and Stoppard. I actually thought the satirical element worked best - the couple squabbling over dirty nappies and relationship issues less so. The huge concern the play demonstrates over crushing state surveillance is sadly right up-to-date. Nothing's changed there.

The acting was all on point and brought out all the fun of the piece. The set design aimed for minimalism but actually was quite tricksy and distracting with actors having to carry props on and off awkwardly all the time. At least in the first half Sally Ambrose entertained us while this was happening with her groovy 60's dance moves. In the second half she became a character in her own right, mooning after Alan Grant's Gary, the gay man struggling against the odds to keep his relationship and child.

Thursday, September 01, 2016

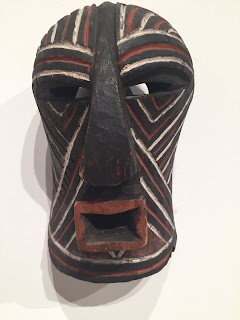

Tribal Art London

The Tribal Arts London fair 2016 is now on in The Mall Galleries until the 4th September. It's a great opportunity to catch an eye-popping spread of Tribal Art all under one roof - areas covered include Africa, Asia and the Pacific. Entry is free but bring your wallet in case you are tempted to buy any of the masks, figurines, bronzes, textiles, ceramics or jewellery on display.

I dropped in to have a look and here are a few of the things that caught my eye. First of all, obviously, some African masks:

(Songye masks from the Congo)

Another Congo mask

A Pende dog mask

A spectacular Sowei/Nowo mask from Sierra Leone

This Fon bronze of a lion with its prey I thought was very elegant.

Exotic head gear!

A fascinating 'power object' - we in the West are more familiar with lovers' locks on bridges - a very different sort of magic I imagine.

The Zulu are very famous as a tribe but actually their art is quite rare - here is a fascinating 19th-century staff with a lion being hunted (top) and a zulu snuff box made out of horn with a metal lid.

Finally, this Ethiopian headrest I thought was striking in its beautiful shape and patina, with highly intriguing metallic adornments and repairs.

I dropped in to have a look and here are a few of the things that caught my eye. First of all, obviously, some African masks:

(Songye masks from the Congo)

Another Congo mask

A Pende dog mask

A spectacular Sowei/Nowo mask from Sierra Leone

This Fon bronze of a lion with its prey I thought was very elegant.

Exotic head gear!

A fascinating 'power object' - we in the West are more familiar with lovers' locks on bridges - a very different sort of magic I imagine.

The Zulu are very famous as a tribe but actually their art is quite rare - here is a fascinating 19th-century staff with a lion being hunted (top) and a zulu snuff box made out of horn with a metal lid.

Finally, this Ethiopian headrest I thought was striking in its beautiful shape and patina, with highly intriguing metallic adornments and repairs.

Tuesday, August 30, 2016

Cut Throat / Camden Fringe

Cut Throat by Jean-Philippe Baril Guerard as adapted by Matt

Cunningham. – London Irish Centre

I caught this play on the penultimate night a week ago now, so this

is a quick late review.

The publicity promised:

"How far can you go in the name of free speech?

Does having the right to speak equal having the right to say everything?

In Cut Throat, the right to speak does not come with a promise that the speech be valid or harmless.

14 characters speak their minds freely about race, religion, relationships, bodies, sex, money, and the meaning of life, without any filter, walking the thin line between comedy and cruelty. An irreverent play that will make you laugh... and cringe."

This was a relatively short, intense play with 14 characters, so

nevertheless quite ambitious as the first production by Trip and Guts Theatre.

The play takes the form of a series of monologues or largely one-sided two-or

three part scenes (mostly loosely unrelated in terms of 'plot' but clearly

related thematically). The audience sits around four sides of a square, and the

actors pop out from the audience's ranks to perform their roles.

All the actors played their parts with evident relish and panache,

and the very wordy play cracks on at a great pace. Stand outs amongst a strong

cast for me were Joseph Rain-Varzaneh as the mugger and Hannah Wilder as the

long-suffering Usher - one of the shortest spoken roles but she appears

throughout the piece as the long-suffering innocent target of the other

characters' nastiness. I can see why this play would appeal to actors -

firstly, each character gets a lot to say and is completely central whilst they

say it, each character has an internal dramatic tension to reveal as the 'real'

inner person breaks through an initial 'polite' or politically-correct outer

shell; and there is external drama in each mini situation too.

We saw this play on the back of Chemsex Monologues, also created

(obviously) around monologues. Monologues are an interesting theatrical device,

notably introduced by Shakespeare to reveal a character's innermost thoughts.

They are at once the most artificial of constructs, breaking any feel of

'realism' on stage but simultaneously the most powerful and direct

communication between actor and audience there can be - really harking back to

ground zero of narration - speaker to listener. There is a tendency in a

monologue for an actor to reach for a kind of declamatory style, which we

thought a bit difficult in Chemsex but this works strongly in Cut Throat. I

think this is because Chemsex the play has realistic fundamental assumptions -

the play is about 'real' characters and plot whereas Cut Throat skews more

conceptual. The characters are very far from realistic, are usually quite easily

identifiable stock contemporary types

- and each scene and character unfolds in a similar way, repeating the

themes of the play almost like an abstract pattern until the climax. My

favourite character, the mugger, is completely surreal, made up as he is of

bravura flights of literary language and philosophy completely alien I would

imagine to any real mugger.

Altogether, a most stimulating evening.

Saturday, August 20, 2016

The Chemsex Monologues

It's not often one hears of an actor playing two roles in different plays at the same time - however, for the last week you could catch Denholm Spurr as Damien/Jean Baptiste in 'The Past is a Tattooed Sailor' by Simon Blow at the Old Red Lion Theatre (through to 27 August) and Nameless in 'The Chemsex Monologues' by Patrick Cash at The King's Head Theatre (last performance tonight).

In fact, make that three roles! (Two different ones in the same play.)

One can only applaud Spurr's energy, commitment and enthusiasm in taking his final bows (after a two hours + performance) at the Old Red Lion and then dashing up Upper Street to The King's Head to don his makeup for Nameless. It would have been fun to catch both performances in a marathon night of theatre, but we took things much more sedately, catching Sailor last weekend (review here) and Chemsex last night after a quick dinner at Belanger on Islington Green.

They are both new gay plays by gay authors performed in pub theatres in Islington simultaneously, but that is where the similarities end.

Sailor is an expansive, nostalgic, traditionally-structured piece whereas Chemsex is much more contemporary in focus and experimental in form. Four narrators appear in sequence with monologues from their individual perspectives on their relationship with Nameless and his story. The audience pieces together Nameless's situation from each fragment - each narrative is slightly unreliable due to their tangential relation to Nameless and the plot line and each character is wrapped up in their own concerns.

This structure gives a sense of urban anonymity and alienation, but also creates a considerable amount of suspense as we follow Nameless's story to its climax. The total separation of the actors also serves to heighten the pathos of Nameless's descent.

The acting was all good, which was so important here when you can't talk of an ensemble. Richard Watkins plays the Narrator - an 'Everygay' sort of character who bookends the play - with breezy charm. Charly Flight is Fag Hag Cath - amusing but very warm and human. Matthew Hodson plays Daniel the Sexual Health Worker - again, a lovable doofus doing his innocent best, a very heart-warming performance. Denholm Spurr's Nameless is the heart of the play and he gives it a terrific performance moving smoothly from humour to the emotional depths.

An urgent and well-considered piece of contemporary theatre; I'm really pleased to have caught it.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)